Futurist Stories of Climate Hope. Plus, How to Love A Chicken!

Sanjana Sekhar, METAMORPHOSIS & Sy Montgomery, WHAT THE CHICKEN KNOWS

Episode Summary

Earth Day is coming up this month, so we get a jump on environmental awareness. From visionary climate futures to the minds of our feathered friends, this episode reminds us that joy, attention, and imagination may be our greatest tools for survival.

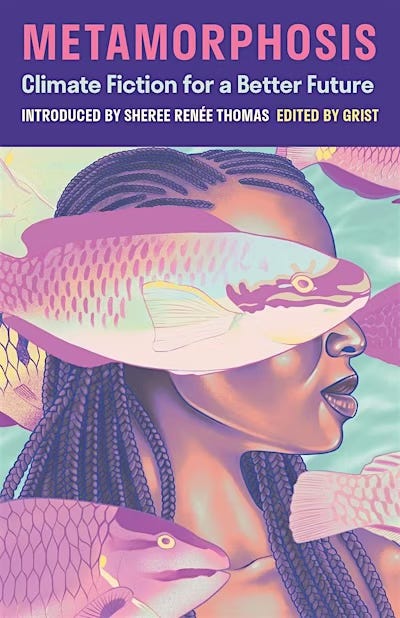

First, we speak with Sanjana Sekhar, editor of Metamorphosis: Climate Fiction for a Better Future, a bold new anthology of climate fiction that reimagines our planet’s future with optimism and justice at its core.

“Ancestral intelligence is the first AI—it's the wisdom that has always known how to live on this planet.” -- Sanjana Sekhar

Then we sit down with beloved naturalist and author Sy Montgomery to explore the surprising world of chickens—yes, chickens—in her delightfully enlightening new book, What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird.

“Almost everything we know about chickens is wrong…chickens are all about relationships.” -- Sy Montgomery

Transcript

Segment 1: Sanjana Sekhar on Metamorphosis: Climate Fiction for a Better Future

Sanjana Sekar, welcome to Writer's Voice.

Thank you so much, Francesca. I'm so happy to be here.

Metamorphosis, climate fiction for a better future. First, tell us about the project, Imagine 2200, climate fiction for future ancestors. Deconstruct that for us.

Yes, great question. So, Imagine 2200 is an ongoing anthology by Grist and they have put out a call out, I believe for the last four years, for writers to submit stories that imagine our human future on earth anytime between now and 2100, sorry, 2200.

And those stories can be in any genre. They can come at the question from any perspective, but the core is to think about how we can maybe have human futures on earth that are stories of survival and stories of hope and stories of joy, basically an antidote to the apocalypse.

And so that narrative, obviously we know the apocalypse narrative is very tied into what a lot of climate storytelling has been for a long time. And so this anthology is really trying to change that.

And this specific book, Metamorphosis, is one of two physical published books that have come out of this larger digital anthology from Grist.

And so this book, Metamorphosis, is published by Milkweed Editions, and it's a book that I believe has 12 short stories in it that are all centered on climate fiction. And a wonderful collection of stories. As I was saying to you before we started recording this interview, it is just such a thrill to have such good fiction be devoted to such an important topic.

Yeah, I think it feels really medicinal, because I think that, I think one of the greatest triumphs of, let's say really the fossil fuel industry, is that it kind of steals our imagination, and it makes us feel like there's no future without it, and there's no way through climate crisis.

And so I think it is one of the greatest, but also most important creative challenges in front of us as human beings to really think about, okay, well, how can we imagine a future where we survive and where we thrive, right?

And we are gonna lose some things, but how do we persist?

And I think that's something, that's a prompt that we have not necessarily had in our mainstream climate narratives really ever. It’s not just the denial of the fossil fuel industry, but that the doomism, which I think is something you just really referenced, that doomism is part of denial and delay and distraction. And this is an anti-dystopian book collection of stories. Talk a little bit about some of the key themes that run through these wonderful stories in Metamorphosis.

Yeah, great question. I think, first of all, I love what you said about this being anti-doomism, anti-apocalypse, et cetera, because I really think you're right. That's exactly what it is. And to me, that's so revolutionary.

So I think that some of the themes that I've noticed run through all these stories, there's always some element of loss, right? I think that's really important to note because I think it's important to say that we're not writing utopian stories either, right? We're acknowledging that there are things that we're gonna lose.

And the real prompt, the question is, and then what, right? And so I think there's that theme where there is always some element of loss in all the stories. You'll see whether it's something related to family, something related to home, something related to food, there's always some reckoning with loss.

But then there's also this through line of the story going beyond that. There is this loss, but there's still life that persists beyond it.

And I think in addition to that, there's a lot of cultural themes, a lot of elements that writers have drawn from their own cultures and cultures that they're inspired by. There's a lot of themes about family and community and really the things that tie us together here on this planet. So you'll see that every story really takes a different angle and has a different flavor, but a lot of these similar ideas come through in all of them.

Another thing that is mentioned, I believe in the introduction, is the idea of ancestral intelligence, the first AI.

I love that.

Yeah, I do too.

What is ancestral intelligence as an inspiration for these stories?

Yeah, I can speak maybe a little bit more specifically to mine just so as not to represent any of the other authors' works and possibly don't want to misrepresent anyone else's work.

But I know that for me and my story, which is called Cabbage Kura, a prognostic autobiography, I lean a lot into generational wisdom.

And I think that really connects to this idea of ancestral intelligence.

I think that there is so much that people have known throughout human history about how to live on this planet in a way that is going to sustain life for continued human enjoyment on this planet.

And I think we have, as a sort of mainstream society, and what I mean by that is like colonial narratives, specifically, and the built world that colonial mythology has created, that mythology strays very far away from a lot of these things that we have always known as humans for thousands and thousands of years, which is obviously why we're seeing such a big shift, right?

And in our relationship to the earth is now, now that relationship and that future is in peril where it wasn't in peril for such a long time.

And I think that's because one of the most simple pieces of ancestral intelligence is that we are all part of this planet.

We're all made of the same stuff.

And if you do something somewhere in this part of this universal soup, it affects the whole soup, right?

It affects everybody.

And so, and everything past and present and future.

And so I think coming back to the spirit of ancestral intelligence is a really important way to guide how we build our future. We're not saying like go back in time. We're not saying go back to different, you know, older technologies and things like that. We're saying, how can we apply the mindset of connectivity as we move forward into the future?

Now, tell us more about your story, Cabbage Koora, the ancestral soup. Tell us about it. It takes place first in 2023. So our past, recent past, and then in 2077.

So this story really was born out of my own personal climate anxiety. I was thinking about the way everything's changing and I live in Los Angeles. And so I was specifically thinking about Los Angeles and I was, you know, kind of scared.

I was like, what is this place gonna look like if I choose to stay here? What will it look like in my own lifetime down the line? And I wasn't sure.

And I think I was very nervous about the ways that the city will change and the ways that life in the city might become harder.

I think I was also feeling nervous that more people in my peer group weren't thinking about this because I think that we often frame climate as something that's gonna affect future generations.

And I think we need to really, really remind people that it's already changed. Like the climate has already changed. It's not a future problem. It has already happened and it's continuing. So it is impacting us currently.

Again, I'm in LA, so the fires just happened last month or a little bit longer ago than that. And it's gonna continue affecting us down the line.

And so what I really was trying to figure out is how am I gonna find my way through the changes that inevitably are going to come?

How am I gonna navigate what I might lose and still find purpose and joy and just a sense of belonging in this city and on this planet?

And when I thought about that, I really started to think about my mom and my grandma, because through our family, and many, many families have a similar story, we've had a lot of migration.

So my grandma in India, my Amama, she experienced India under British colonialism, right?

That ended when she was a really young child, but she has seen that part of India's history.

And my mom has migrated from India to America, so she's far away from her mom, and they navigate that in their relationship, and I therefore navigate that as well.

And so I was thinking, I was like, okay, what am I gonna do if, and now I live far away from my mom, so what am I gonna do if I have kids one day and they move far away from me?

How am I gonna deal with that?

And I realized that there's a bit of a through line in all the women in my family, like we've all experienced migration, we've all experienced loss in some way, and we are still some of the most joyful people I know.

We laugh together, we use technology to connect with each other, and a lot of the ways that we connect on technology is what are you eating? What are you making? Is food related?

And so just tapping into the ways that there's a blueprint for navigating uncertain times, and that blueprint already lives within my DNA through these generations of women in my family, and also is a shared experience that a lot of other people can resonate with as well.

And for those of us who are looking for those ways to navigate through these times, and not just climate change, but of course, fundamentally related to it, the lack of democracy in every single way, what are the most important lessons that you drew from your family?

I love this question.

My biggest lesson, honestly, is that we have to find joy like it's our jobs.

I've been saying this for as long as I can think of now, because I think that's the one thing that my family has taught me, is that struggle is a part of life, and there are communities around the world who have experienced that and who have survived that.

And I think of any oppressed community, any community that has experienced colonialism, either past or present, the survival of those communities is, first of all, just a testament to the way that, in the face of hardship, they dig their heels in for the better world that they know exists.

And I think that's something that I've seen in my family as well, is that you have to be so connected to joy because you have to know.

We typically are very familiar with what we're fighting against, right?

We know what the demons are, but we have to also be really, really familiar with what we're fighting for, because otherwise we cannot sustain ourselves in the face of whatever scary things are going on.

And so that is, to me, my biggest lesson.

Like this entire story, the Cabbage Koora story that I wrote, the seed of it was based on this FaceTime call that I had with my mom and my grandma.

We're all three in different places in the world, and we're on FaceTime this one day, and we're just cracking up because my grandma is trying to show us a cabbage that she just got from the vegetable guy in the morning.

And she, even though we've been FaceTiming with each other for years, she still struggles sometimes with like where to point the camera.

And so she's pointing it at her ceiling, and she's like, can you see the cabbage?

Can you see the cabbage?

And we're just dying laughing because we're literally just looking at her ceiling.

And then eventually we just see the small piece of a leaf flash by the screen.

And we're like, oh, we see the cabbage.

And to me, I was just sitting there in that moment.

And I was like, I'm so, on the one hand, I'm so sad that I live 8,000 miles away from my grandma because, you know, and a lot of that was like economically driven.

My mom felt like she had to leave because there wasn't opportunity for us in India the way that she wanted.

And that's because of colonialism, right, and the resources that were taken from that land.

So she had to leave.

And I'm like, OK, I might have to deal with that at some point in my life, either me leaving my mom or my future kids one day moving away from me.

But we still have this joy where we're like on FaceTime, far away from each other, cracking up about the simplest thing.

And I think that is what we have to really, really persistently and stubbornly connect to in these times especially. I so love that.

Because to have joy in our hearts is to then really eject the seemingly ever-present parasitic presence of Trump and fascism.

And so it really is an exercise that we need to undertake every day.

So one of my, I mean, there were so many wonderful stories here. But one that really was like had me cheering at the end was called A Holdout in Northern California Designated Wildcraft Zone.

Yeah, I loved that one.

This is a story about California has designated wildlife areas to rewild.

And one gets the sense that this was a billionaire-funded project or something where humans had to leave all those areas and concentrate into city-states.

And one old woman is a holdout.

And what was so interesting for me and that I loved is that I guess AI has developed to the point where it even has a conscience and a sense of compassion.

What did you love about this story?

This is honestly one of my favorite stories because I feel like it did such a smart job of sort of like secretly talking about things that have actually happened in the past in the name of conservation and at the hands of very wealthy people, but putting it in the context of the future in a way that is so believable.

Like I could actually see this happening, right?

And I think what really stuck out to me was this idea that a really wealthy person can buy a parcel of land and kick everybody who lives there off the land and call that conservation.

That has been the literal conservation movement since, you know, like the fifties, right?

And a lot of that comes from a direct, like, for example across the continent of Africa, as countries gained their independence, we start to see a surge in these oftentimes nonprofits or individuals who buy parcels of land and reserve them as game reserves.

So it's kind of a way of continuing to control land and resources in a country that has just fought for its independence.

And it happens even now with like carbon credits, for example, where if you are buying something like you're buying a flight and then you're buying, okay, let me, you know, let me try and offset my carbon emissions from this flight.

So you click the little box, because as a consumer, they're not going to tell you all this, but then what's happening behind the scenes is there is some parcel of land somewhere, not in, you know, the, so to speak global North that has been bought up by this company.

And everyone who lives there has been kicked off.

And that is now being dedicated to growing trees or something.

But the story that you're not being told is that we took someone's home for that.

It's also even the story of America's national parks, right, which are incredible spaces, but have had people living there for thousands of years.

And so I think this story to me, like it's set in the future, but it's actually just a continuation of what the so-called conservation movement has been doing for decades now.

And that really stood out to me because I was like, this is really smart.

It's such a smart way to be like, if you put it in the future, suddenly it feels really uncomfortable.

But then when you look around and you realize it's been happening this whole time, you're like, we really got to change that.

That cannot be what we consider carbon credits or conservation or any of that, right?

Cause it's not a real solution to the problem and it actually makes it worse.

And so what is a solution? …Maybe Audre Lorde said this, that there isn't a solution, there's thousands.

I need to really remember who said that, but I love that quote because I think oftentimes working in this space, people will ask me, okay, so what is the answer?

And I'm like, there isn't an answer.

There isn't one answer, right?

There's thousands of answers because there's so many people and there's so many different kinds of knowledges and there's so many different ecosystems.

Like we need to localize in so many ways, right?

We need to look around us. We need to be participating in our local elections, our local mutual aid groups. We need to be participating in our own friend groups and families, and that is where we find solutions.

And of course it needs to happen at a large scale as well, but I don't think that it's one or the other.

And I think that culture, which is all of us, needs to change and push policy as well, right?

Those things need to happen simultaneously.

And so I think a lot of it is just asking questions, right?

And there's gonna be complexities.

There's gonna be contradictions as well.

For example, we need to move off of, we need to move off of fossil fuel that involves things like wind and solar, which involves mining of things like lithium and cobalt, right?

Everything is from the earth.

So I think the question is, how do we build better business models?

How do we think about who our stakeholders are?

How do we have these conversations and bring these issues to people's attention, to people in power's attention, and make sure that they know what we're okay with and what we're not okay with.

That's actually an idea that also appears in one of my other favorite stories, To Labor for the Hive, because in that story, even though she's not a major character and we never really meet her, there is an old woman who's talked about who was part of the coal economy.

This takes place in China in a region that had been based on coal mining. And there is a discussion of, I think there's at one point where the question comes up, was it really worth it for her to lose her purpose in life? And she may even ask that I think of one of the characters, was it worth it to make that transition away?

And the answer is yes, but as you said, it's complicated.

Yeah, first of all, another story that just, I think I was crying in that one.

That one was so beautifully written.

What I think about when I think of that is how, because I think that story in particular also talks about loneliness a lot.

And I resonate with that in the sense that I think we need to do a better job of seeing each other.

And when it comes to something like a transition for someone who has been in an industry for a long time that now is not a financial future or that people are moving away from, I think we need to just make sure that those people feel seen and held and that they are, that we are allowing everyone a dignified transition into something that is a financial future and that is a sustainable industry and job for them.

Because at the end of the day, I think about this a lot, especially regarding what's going on.

I think it was AOC who said, it's not about left versus right, it's about top versus bottom.

And the reason that I think about that is in a lot of ways, I think that politics and values are different.

I think values are sort of like the body and politics is more like the costume.

And we need to do a better job of seeing that in each other and realizing that our values are actually very aligned and just sort of like holding each other as we navigate uncertain times versus getting upset with each other or judging each other, like to judge someone for working in coal at one point or anything like that.

That's what I loved about the story is it didn't take that attitude.

It was very like loving, you know, and I think that is what we need more of.

Absolutely.

Well, Sanjana Sekar, it has just been a delight to talk with you about this wonderful collection of stories. You are such an important person in this space and really inspirational. You are a founder of Garmi. Just briefly tell us what that is.

Sure, thank you for that question.

Garmi is a sort of experimental storytelling studio. Right now it's mostly a newsletter, but we're expanding into a few other modalities of storytelling, so stay tuned.

But the whole mission of Garmi is to make climate action irresistible. And my phrase that I love saying that Garmi sort of built on is the planet is getting hotter, but so am I. That's great.

In a good way.

Yeah, exactly. It's a little play on those words because Garmi actually means heat in Hindi. And so it's a play on the idea of heat because heat can be destructive, but heat can also be transformational.

Absolutely. Thanks again. It's just been a privilege to talk with you.

Thank you so much, Francesca. It's been such a pleasure being here.

Segment 2: Sy Montgomery on What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird

Sy Montgomery, welcome back to Writer's Voice.

Thanks so much for having me.

I really loved this short but totally charming and informative book, What the Chicken Knows, a new appreciation of the world's most familiar bird.

You start the book with an aggressive rooster about whom you were given some very sage advice about what to do with him. And I was so startled and I just totally loved it.So tell our audience what that was.

Well we actually, we mostly had a feminist utopia in our barnyard.

We mostly had just hens.

But sometimes when we ordered from a particular hatchery, they'd give a free exotic chick and it always turned out to be a rooster.

So and I love roosters.

I loved the little chicks as they grew up and we thought, you know, our first rooster was going to make a fine one.

But what often happens is roosters in an effort to protect their ladies can become aggressive.

And what do you do then?

Well back then, I did not know what to do other than give the rooster to another farmer who needed a rooster.

Obviously his retirement plan at our house was not going to involve the stew pot.

But many years later, I discovered living just down the street from me was a family who operated a rooster rescue because so many people dump their roosters.

And they have discovered how to turn an obnoxious and overly aggressive rooster into a perfect gentleman.

And the solution is absolutely counterintuitive.

What do you do when this like scary direct relative of dinosaurs comes at you bearing these pointy spurs?

You're supposed to pick him up and cuddle him.

And that sounds insane, but it actually works because I have met the gentlemen roosters at the rooster rescue and nicer birds you could never find.

And it's all from her methods of picking up the rooster, cuddle him, take him with you everywhere you're going to do all of your chores.

Keep him under your sweater if you if you want.

If it's warm out, you know, maybe put his feet with the spurs and a towel and eventually he's going to fall in love with you and he'll never attack you or your children again.

It's such a beautiful story because what it really says is that love is the answer.

And love is the answer.

You also say that almost everything we know about chickens is wrong. So what are the main things we've gotten wrong about chickens?

Well many people have told me, oh, chickens, aren't they dirty?

Aren't they stupid?

Aren't they so dumb that you cut off their head and they'll run around like a chicken with its head cut off?

Isn't that proof that they're really dumb?

Well, goodness, I think that would be a pretty neat trick to do.

Not evidence that someone was dumb.

Chickens actually are very affectionate, very smart and superbly clean.

But the idea that we have that they're stupid or mean or dirty, I think this comes from people who have met them on factory farms, which is like a gulag.

It's a gulag with no space.

So it's like a prison camp and no one's at their best in the prison camp.

So when you get to know chickens, when you get to watch chickens and see chickens, you see how social they are.

You see that they recognize not only you, but everyone in your family.

Scientific tests have shown that each chicken can recognize a hundred different faces.

And sometimes when I go into town and meet someone who came to one of my book signings and can't place them, I think the chickens have got something on me.

And they're also very affectionate because chickens are all about relationships.

It matters who you sleep next to on your perch at night.

Within every flock, every flock is its own little society.

Everyone knows everybody else, knows about everybody else.

You have your favorites and then you have the others that you might not want to see so much.

If you're lucky enough to have a rooster, you have a protector who's going to look out for you, who's going to call when there's delicious food.

He'll even step back and his ladies eat first and he will not.

So it's a whole different world out there and often so close at hand that even if you don't have chickens in your yard, probably someone you know does.

You know, it's so interesting the range of intelligence that they have. So the relationships is one thing, but you know, they pass the mirror test, which I think only very few other animals do, although maybe it's because we're not doing the right kind of mirror test. Did you point that out?

Yes.

You're so right, Francesca.

This is exactly it.

And I think this is the case when we apply a lot of intelligence tests to animals.

We're not asking the question in a biologically relevant way.

I have seen orangutans presented with, here's a bunch of square pegs and square holes, and the orangutan doesn't put the square pegs in the square holes, a chimp will.

So does that mean the orangutan is stupid?

No, it just means that he doesn't see the need to do that.

So if we want to test intelligence, we have to find a way to ask the question in a way that means something to the animal.

And the way this ingenious researcher tested roosters to see if they passed the mirror test was, now if the rooster saw its reflection and thought it was another rooster, would the rooster talk to his reflection?

Would he call out to his reflection and say, oh, there's a predator coming?

Or would he go silent?

Well they presented mirrors to roosters so they could get used to them, and then they put them in these two different situations.

One, the rooster just saw a mirror that reflected his own image.

And two, the rooster could see other roosters.

And then they showed a hawk flying overhead.

And when there were other roosters watching him, he would call and tell them about that predator.

But when all he saw was his own reflection, he wasn't going to call out.

That was just going to alert the predator to his presence.

So that was a really smart way to see if the rooster understood his reflection was not another real rooster, but just his own image being reflected back.

And this is so interesting because what it really points to is an anthropomorphic bias that we have when we're studying animals. And often the anthropomorphic bias has been one that says animals are stupid. And you know, the Descartesian notion that they're just like machines, so they're here for our use. You know, it's all very self-serving.

Or it could be the other extreme ascribing true human characteristics to roosters.And that may be true to a certain degree because we're all animals and we evolved ultimately from the same living beings. But you say that, you know, really different animals have different cultures in effect and that we need to take a different approach.I wonder if you could draw that out a little bit, explain it further.

Well, the problem of anthropomorphizing, that says that when an animal shows emotion or intellect, we're just pretending, we're projecting our own emotions or our own intellect onto that animal as if we're the only ones that ever had emotions or intellect.

Well emotions and intellect help us survive, but it helps everyone else survive too.

Learning and memory is essential for most animals and it may be essential to other creatures who are not animals as well.

Interestingly, even slime molds appear to be able to figure stuff out in some way that we don't understand.

Bodies can communicate with one another, not vocally, but through the mycelia, the fungal hyphae that connect roots to roots.

So there's a lot going on that we don't understand.

But to assume that we're the only ones who can think and feel and know is crazy.

It is to deny the existence of evolution, it is to refute every creation story in every human culture also.

But not everyone thinks in the same way we do, or else fish would beg to be taken out of the water, and your dog would not lick under her tail during your dinner party.

So I say, you know, let's celebrate our samenesses and let's celebrate our differences too.

Yes, exactly. And I think that, you know, that's really the subtext of all your books is the deep respect that paying attention to something that is not ourselves brings.

Yes, absolutely.

And it makes us, I think, feel more at home and embedded in our home than if we pretend we're on some high pinnacle far away from everything else.

Nobody wants to be alone like that.

And I feel, you know, supported and enriched by all these other lives going on around me.

And I feel connected to sensations I can't really experience, but that I know others can experience.

For example, birds can see ultraviolet light.

Well, that just illuminates my life, knowing that birds are seeing what is invisible to me, but is nonetheless very, very real.

You know, and that goes to something we were just talking about, in fact, before we started recording this conversation. And that is, you know, the movement to bring more wildlife habitat to our own spaces and how that creates a kind of diversity.

And I know what you mean. My life has just been incredibly enriched by the fact that now, when I saw a tiny little bug, an ant this morning, a really, really tiny ant, and instead of just passing it over and not thinking the next thing about it, I thought about what it might be thinking as it was progressing around my new little garden bed.

Oh, wow. I bet he was happy. I bet he was happy that you made this new garden bed.

Yeah, but it becomes automatic then when you get to have the habit, as I know that you have because you write such exquisitely sensitive books about this.

Oh, you're so nice to say that.

Of seeing what's around you, that connection, I think that's really the heart of the story.

Yeah. I mean, that's why I wanted to write about chickens in that this is the world's most familiar bird.

Many people can't identify a robin or tell it from a crow, but they'll know a chicken because there was the chicken right on the Kellogg's Corn Flakes box, right?

There's something like four chickens in the world for every person.

And when you realize that an animal this common can be a source of wildness and wonder, that is a fabulous thing.

Wildness and wonder. Give us some examples from your own flock that you raised.

One of the things that I really loved about having my flock was standing among them at night when everyone was roosting and everyone was kind of just gently vocalizing their contentment at being with their friends.

And this was a very lovely thing to realize that we share this with these direct descendants of the theropod dinosaurs.

That relationship, that friendships, that sweet comfort of being among those you love, this is something shared by wide swathes of creation.

Many, many different taxa enjoy just what we enjoy, which is fabulous.

Then there were times that my chickens just blew me away with their smarts.

When they were babies, we raised them in my office and then we took them outside to be in the coop that had been built for them.

But we wanted them to be able to free range so there was no fence.

I asked my friend Gretchen, who'd given me the birds, how are they going to figure out that they live here?

How are they not going to just wander out of the coop and disappear into the woods where they will be eaten by predators?

And the reason I asked this was that pretty much that's what happened to me every time my family moved when I was a child.

I remember getting lost in my own backyard.

How did the chickens figure this out?

Well, Gretchen didn't know, but she assured me they will figure it out, don't worry.

And not only was I able to let them out the very next day and have them return right into their coop as it began to get dark, but they also intuited the boundaries of our property.

Right next to their coop is a low stone wall and then our neighbor's yard.

Now, that low stone wall can easily be walked over or flown over if you're a bird, but somehow without my ever having told them this, these birds figured out that was our property and not to go into the neighbor's yard.

And this persisted for years until that neighbor moved away.

New neighbors came in, and the two little girls who lived in the house started hanging out with us every single day to play with the chickens, play with our border collie, and particularly play with our pig, Christopher Hogwood.

So they were over our house like every day.

We were over their house like every day.

And the chickens realized before I did what had happened.

We had become one family.

And that was when they started hopping over that low stone wall and totally annexed their property as if it was their own.

And also you talk about how chickens have specific words. And in fact, one chicken in the book actually named your housemate at the time who also had a flock of chickens. Talk about chickens and language.

Oh my gosh.

Yeah.

This is actually, this was first reported by my friend, Melissa, who has a wonderful book called How to Speak Chicken.

And she reported this. One of her chickens, whose name was Tilly, it was her very favorite chicken, made this sound that no one else seemed to ever make.

And she was telling me about this at an American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting that we were both attending as we were both getting literary awards. And her literary award was for How to Speak Chicken.

Anyway, she figured out that this sound, it was a phrase actually, it kind of went, bah, bah, bah, bah, kind of like that. But that was Tilly's name for Melissa. And Tilly only said it when Melissa was coming.

Well, before Tilly died, she actually taught the name to others in the flock. So the name that Tilly made up for Melissa still persists. And what do we call that kind of thing? We call that culture. So I absolutely adore that.

Now I learned a lot when we got a new tenant who came in with her own flock of chickens. That was when I could see very clearly that each flock has their own culture.

Her flock, she called the Rangers, and they were ready to rumble. They were a riot.

They would make up games to play with her. Some of them played tricks on the other chickens. Some of them learned to essentially lie as a prank, to claim, like, look, look, look, there's delicious food, delicious food, delicious food.

And then the other chickens would come running over, and then the chicken that was calling out would eat it before they could get to it and thought that was hilarious.

And her chickens often said sweet nothings just to her that she never heard them say otherwise.

The chicken would sit in her lap and say, duff, duff, duff. No one else ever said that.

But most important to me, the difference between the two flocks, was that my flock was this peaceful utopian, you know, everyone got along, there were no mean girls, you know.

There's a pecking order, but very little pecking in my flock.

Hers, everyone was ready to beat up on everybody else if they wanted to and they hated my chickens.

So even though her chickens had a fence that separated them from my chickens, my chickens didn't even want to be near them.

So what did they do? They just moved into the neighbor's yard, pretty much, and only slept at our house until the rangers, my tenant's flock, actually moved away when she was ready to get married.

So they just said, I'm out of here. I don't want any part of you.

But it was so funny to see her rangers rumbling and insulting my chickens.

They would stamp, they would erect their feathers, they would drag their wings menacingly in the dirt. And you could see they were just saying, I'm going to beat you up.

You know, all of this, of this really charming book, What the Chicken Knows, Sy Montgomery, brings to mind, we mentioned it before, you mentioned the gulags, you know, industrial, raising chickens industrially. It just makes my heart hurt because it's so unconscionable that we would subject such intelligent, charming, affectionate beings to this monstrosity.

I just wonder, what were you thinking as you were writing this book and as you have your chickens? I mean, I'm sure that wasn't ever that far from your mind, the whole way that chickens live in this society.

Absolutely, absolutely.

And rather than, you know, fuss at people on the pages, it was my hope that they would close the pages of my book and say, I'm not going to reward the torture of creatures like this with my money.

Now, there's many ways that you can avoid buying chickens from these horrible facilities and the chicken's going to cost a little more.

Or you can avoid eating chicken at all.

And there's just so many, I've been a vegetarian for over 40 years, and there's so many other delicious things to eat that don't cause someone who loves their life to lose their life forever, much less under horrible circumstances.

And eggs, I mean, this is interesting.

There's ways you can buy pasture-raised eggs.

There's organic eggs, which actually means nothing about the humane treatment of the animals.

And there is free-range eggs, but that just means that there has to be a little door through which the chicken could go outside if it wanted to.

What they find outside and whether it's any good at all isn't said.

Pasture-raised means the chickens are actually going outside, living in the sunshine, able to eat bugs and grass.

So if you do eat and buy eggs, go to the grocery store and get the pasture-raised eggs or get them from a neighbor.

And that's what I do, because we no longer have our chickens. We had to give up our flock. So many predators have returned to New Hampshire. And the way our barn was set up, it's really closer to our neighbors than our house. I can't see the barnyard from my house. I see the other part of the barn. And I wanted my ladies to be able to free-range.

Down the street, I have a wonderful neighbor, Julie Brown, and her house is set up that her front door just opens out on her barnyard.

And she has two great kids who are often playing in the yard.

She spends a lot of time in her yard gardening.

So her chickens can be out all the time and have a great life.

But the way our place was set up, they were all getting picked off by foxes, by mink, by weasels, by hawks, by bobcats.

My husband Howard says, if you want to see wildlife in New Hampshire, get some chickens because they're going to be on the heels of the girls.

Yeah, everybody loves chicken.

Yeah, everything tastes like chicken too.

And you point out in the book that that's actually a good thing, not that everybody likes chicken, but that the predators are coming back.

Yeah, it totally is because our ecosystem is healing. We need all of these creatures for our world to be whole. And if you're a scientist, you understand that. If you're a religious person, you also understand that. I don't know better than the creator him or herself, so I'll go with whatever he or she came up with, which is to have all of these different kinds of life living around us. So I don't resent all of these predators for coming back.

There's easy workarounds for humans, and that is the case with almost everything. You don't even have to go to a great deal of effort to find either a substitute for eggs or an alternate way to get eggs that were humanely produced. None of this stuff is particularly difficult to come up with.

I realize how expensive eggs are and that people are really upset about this, understandably, but you know what you can use instead of those expensive eggs in a lot of things, including baking?

You can use the water in a can of garbanzo beans that you would throw down the garbage disposal. You'd throw it down the sink.

There's so many easy, cheap ways to come up with a substitute that doesn't hurt anybody.

So I say, you know, let's find those ways and let's keep our world whole. Let's use our good brains to make a saner, more compassionate, healthier world.

Well, hear, hear. And that's a great tip. I'm going to use it. I'd never heard that one before.

Yeah. It's, you can actually find it, I mean, just Google. It's actually got a name, aqua something or another. But say “egg substitute garbanzo beans.” Garbanzo beans are also called chickpeas. You can try chickpeas and it'll come up with this. And this is something you'd throw away. And I mean, chickpeas are great. You can use the chickpeas in a million wonderful things. But the fact that you can use this unwanted juice it's packed in, that's fabulous.

And there's lots of other workarounds as well. There's a million things that you can use instead of the flesh of a chicken in most recipes that will taste just as good and be even healthier for you and way healthier for chickens.

Well, it was such a delight to read this wonderful book, What the Chicken Knows.

I do have one more question, which is, you've written about an octopus, you've written about a pig, you've written about chickens, you've written about, was it hawks or falcons?

Yeah, hawks.

What is your next animal, if you have one to write about?

Well, the next book that's coming out is going to come out in September, and it's going to be another turtle book with a fabulous artist, Matt Patterson.

But I'm also writing a series of essays for a National Geographic book of Joel Sartori's iconic portraits of animals called the photo arc.

I'm writing a book for younger readers, not itty bitties, but school children, about an expedition I got to do last year scuba diving with giant manta rays, which was awesome.

And I'm also working on a book with Matt about caterpillars, who are celebrated for turning into butterflies and moths, which is a great trick.

But before they do that, they have some dazzling superpowers, so they deserve a book of their own.

Oh my goodness. What an embarrassment of riches. Well, I'd love to talk with you about those books.

Boy, I will talk to you about anything, anytime, always, because you are a treasure.

Oh, thank you so much. And likewise, I feel the same.

Thank you, Sy Montgomery.

Oh, what a pleasure.